When I started my family research in 2009, it was all lopsided. My mother’s family had annual reunions and shared churches and a huge piece of paper with all of our names on it in trim little boxes. I remember one year at the family reunion someone had tacked up the family tree on a wall of the church’s banquet room. Photos of most of the family were taped up next to their entry on the tree. I watched as my relatives would bring their son or granddaughter to the chart and show them the box in which their name was written and then trace their branch up the chart. Inevitably, they would turn to the room, and the older person would point at various people the child knew and tell them their relationship.

“That’s your great-aunt Margaret, Nicky. She’s your papa’s sister. See her over in the flowered dress talking to daddy?”

It was nice. If anyone felt insecure about their place in the family, they could look to the large tree drawn on the wall and know that they belong. It felt as if the ties between us were tangled beneath the grid of tables filling the room.

My favorite photos of them are of when they were young. Seeing my grandparents, my aunt and uncle, my parents before kids and divorces and funerals. All of the lifetimes they had before I knew them.

That was my mother’s side. The known side. My father’s side was hazier.

Dad grew up in foster care from age 8. He knew his brother, sister, half-sisters and half-brother, parents, aunts, and uncles lived in town, but he also knew he barely spoke to any of them, let alone lived with them. He knew his mother’s last name because it was written on his birth certificate. (We would later discover that last name was incorrect.) There were no photographs of these people, no stories. Occasionally Dad would mention something about his childhood—how his mom made the best blackberry cobbler or how the horses at the job he held in high school always seemed to buck when it was his turn to clean their stables, but he never lingered long in those memories.

I started researching his family with very little to go on. The first names of his mother and siblings. Found out dad had close family members living all around where he grew up. Found out I had deep roots in two unfamiliar states: Iowa and Missouri. I was lucky there was a huge network of researchers on that side of my family who posted to Ancestry. It didn’t take long for me to discover photos of my grandparents.

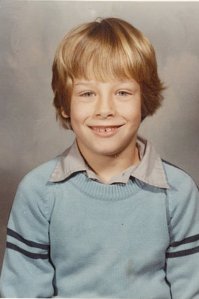

That first glimpse was a lightning strike. There was no doubt they were family. Seeing their familiar faces was like meeting ghosts who had haunted my childhood home. I even found a photograph of my dad as a boy. In all the shuffling around of his childhood, he hadn’t held onto his keepsakes.

These are my favorite photos of my dad’s side. The unknown side. That light I’d felt when I’d seen my grandparents’ faces and recognized my dad, my brothers, myself in them is what keeps me researching my family tree.

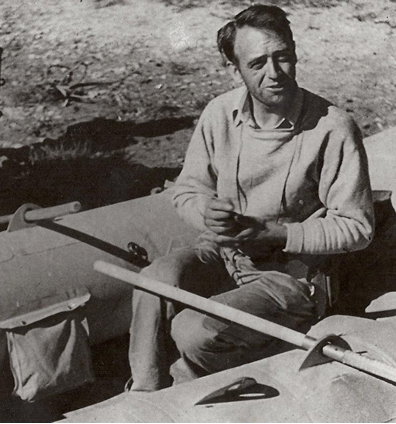

(The featured photo of this post is my maternal grandfather (in the hat) with his younger brothers, c. 1918.)

Writing for Amy Johnson Crow’s #52Ancestors.