Those glazed over eyes.

You know what I mean: that moment at a party when you realize you can’t remember how long you’ve been talking, and everyone that was listening is now either staring at hors d’oeuvres or smiling politely while internally wording their tweets about that boring guy who droned on for half an hour about the pros and cons of various genealogy tv shows.

It’s not happening to me as often lately, because I’ve taken genealogy off my list of topics to discuss with mixed company.

I know what you’re thinking: Screw that! Talk about what you want to talk about, and if they don’t like it, then they can just walk away.

Yes. But looking at it from the listener’s perspective, I get it. I remember history class, all those arbitrary dates and names. As someone who is not into sports, I have often found myself concentrating on suppressing a yawn at the back of my throat as some person I just met goes on and on about batting averages and World Series and I don’t even know what else.

I’ve realized that me and Sports Person were both making a mistake in presentation. We were trying to engage people with the particulars of our passions and not giving them any inkling as to what’s fueling it. Getting people interested in potentially eye-glazing subjects is all about the packaging:

“Hey, Sports Person, what is it about watching sports that interests you so much?”

“I guess I just really love seeing evidence of what people can do when they pull together for a common goal. I love following the stories of the individual players, knowing where they came from and how they found a place on a team, many of them having to travel to other countries in order to do so. Plus I connect to people when I see them doing something they’re passionate about.”

“Oh. I can completely get behind that. That’s exactly why I like genealogy. Tell me more about this sportsball thing.”

Yeah, that conversation would never happen around an hors d’oeuvres table…or anywhere else for that matter. That’s why I’m choosing to keep the subject in my back pocket except when I’m around other family historians. When I do mention it at parties, I try to keep it short and not bury the lede. But, since I have you here, let me tell you what I have decided to say:

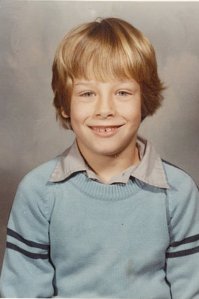

My father didn’t know his parents. I started researching my family to find out more about them. I discovered stories and pictures and documents that filled in the holes of my family’s story. One photo I found was of my father as a little boy, a phase in his life that I’d never seen evidence of before.

I was surprised to find out I actually looked quite a bit like him (a fact that wasn’t obvious when I was a kid and he was a brown-haired and bearded adult).

Then I got a photo of my dad’s mother.

I saw where my father and I got our blue eyes, and the way we set our jaw when we smile. I was dumbfounded by how obvious the connection was. I realized that the features I see in the mirror are hand-me-downs; they are not mine at all.

I learned that my grandmother lived in southern Missouri, and I read her account of living in the Dustbowl during the Great Depression. It made real those seemingly arbitrary dates and events I studied in high school: My family was there; they lived through it. I wish I’d listened better to those lessons in class, because they very much shaped my father’s upbringing.

That’s what I would say.

Or I might just tell the story of what happened to me last night. I received my paternal grandfather’s Social Security Application in the mail. The information it provides is fairly innocuous, but it is the first document I’ve uncovered that is written in his own hand. His signature ends the form like a period. The distinctive capital R, the serpentine curls of the e and s at the end of our shared last name.

It is my own handwriting.

The man passed away 2 years before I was born, and my father did not grow up in his house. But there it was plain as day: undeniable evidence of my connection to him.

To think that the chemicals in our cells can determine even the smallest details about our lives, like how we write our names. It’s just baffling to me. And these reminders that who I am is not completely in my control are comforting. Destiny, and all that. Making more of those connections inspires me to keep searching through my own history and to listen to the histories of other people’s families.