My great-grandfather through his daughter.

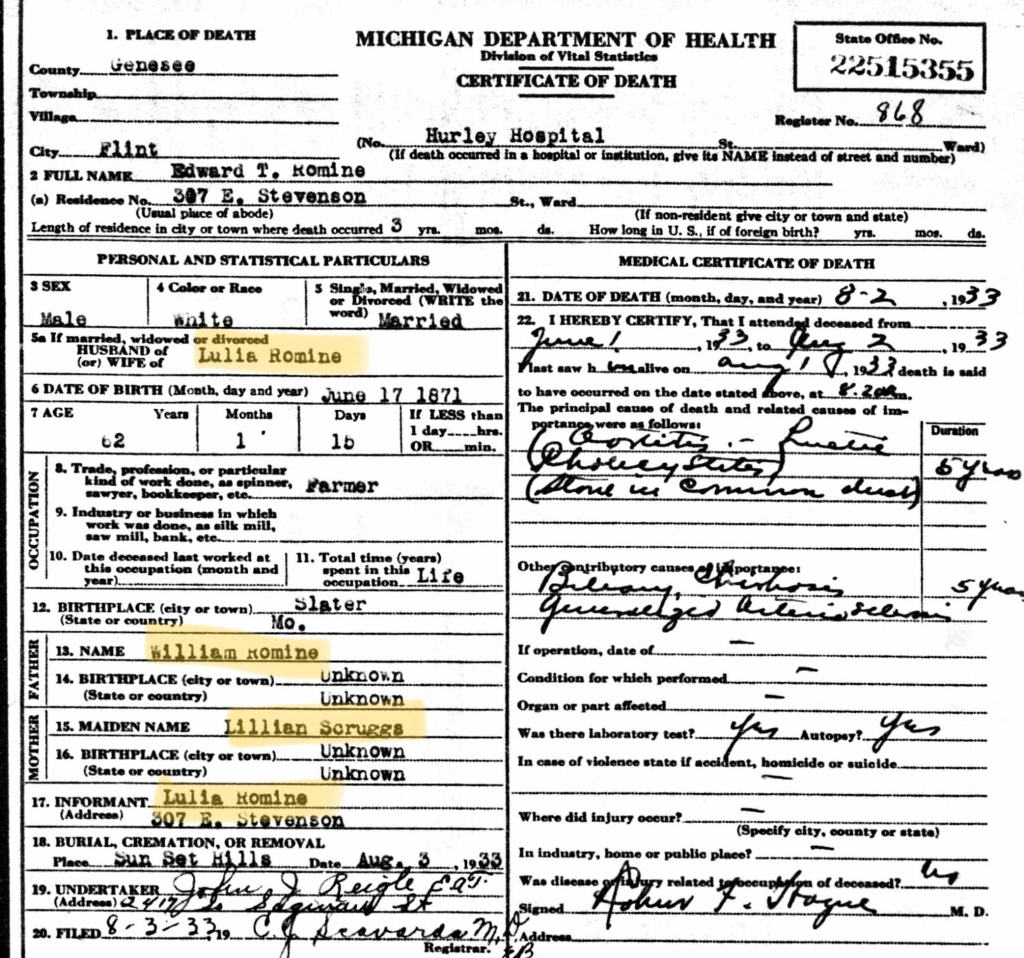

Albert Clayton, whose name was written down most often as A.C., Romine was born on August 15, 1898, in the tiny town of Frisco, Stoddard County, Missouri. His father Edward Romine was a farmer, his mother Fanny Grace’s family farmed just down the street, as did his grandfather Samuel Romine.

Fanny likely died when AC was 3 years old. His father married Louella Cunningham Rayborn in 1902. In future records, she is listed as his mother. However, on his application for Social Security, AC lists Fanny as his mother in his own writing.

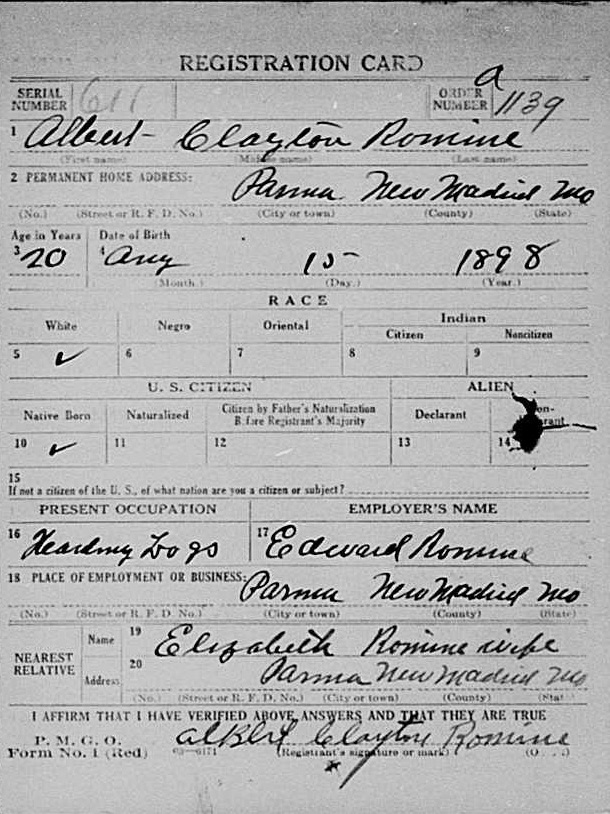

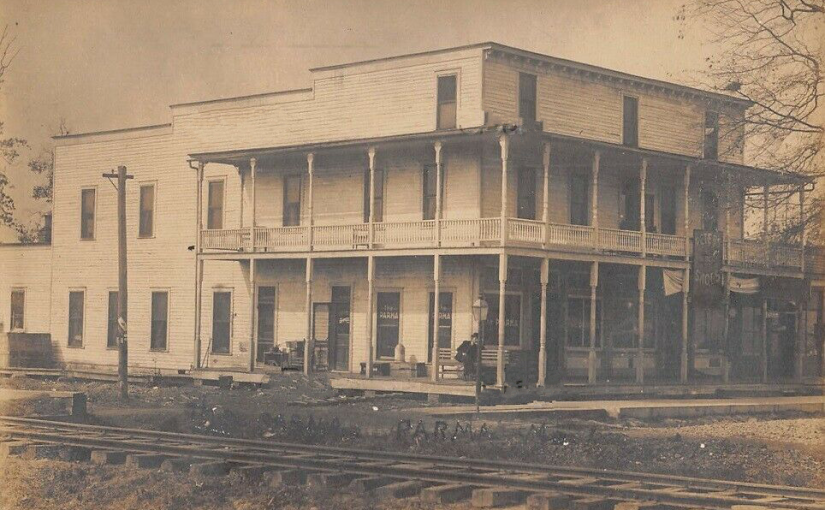

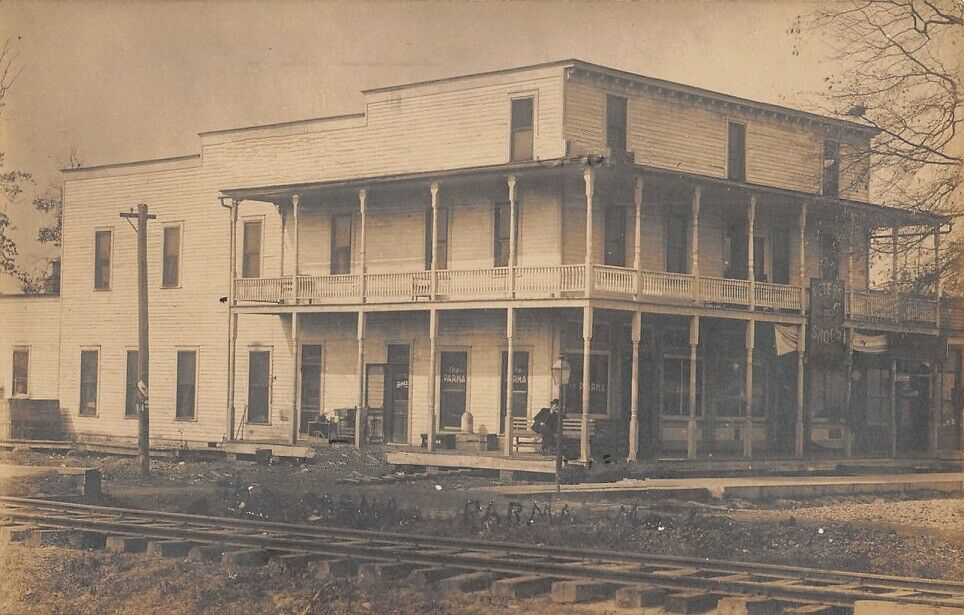

Albert married Elizabeth Minnie Lewis on August 16, 1917 in Parma, Missouri. A year later, his WWI Draft card lists Elizabeth as his wife and his father as his employer in a timber company. Unfortunately, A.C. didn’t stick around long enough to raise their three children.

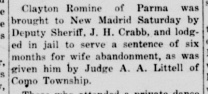

In 1920, Elizabeth is found in the census living with her parents in Parma, Missouri. Clayton is nowhere to be found. His being missing from records becomes a theme.

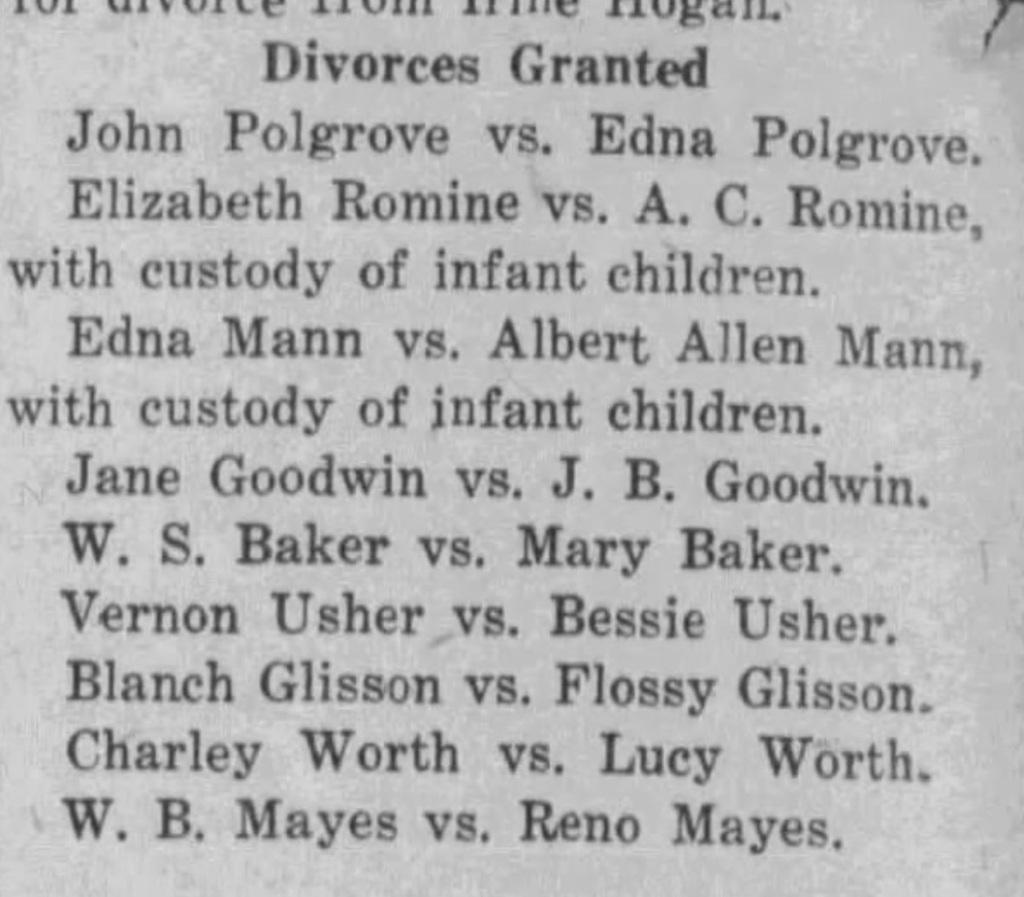

Elizabeth and Clayton divorced even though he never appeared in court when he was called to. He marries Mellie Herndon Zinzel in New Madrid County, Missouri, in 1932.

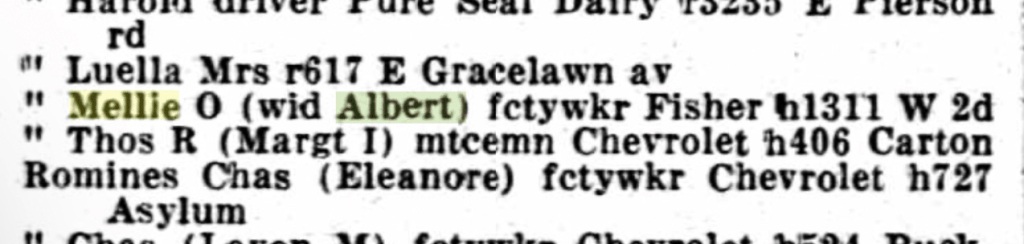

He can’t be found anywhere in the 1920 and 1930 census. In the 1940 census, A.C., Mellie, and stepdaughter Helen Zinzel live in East Prairie, Missouri, just north of New Madrid. Considering AC can be found in the Flint City Directory in 1939 and 1941 living in Flint, it seems like he moved around a lot. Probably to follow work.

An address he tended to go back to every two or three years was 1311 2nd Avenue in Flint. This is the house his father had bought when they first moved to the area. His stepbrothers and stepsisters are often listed there too.

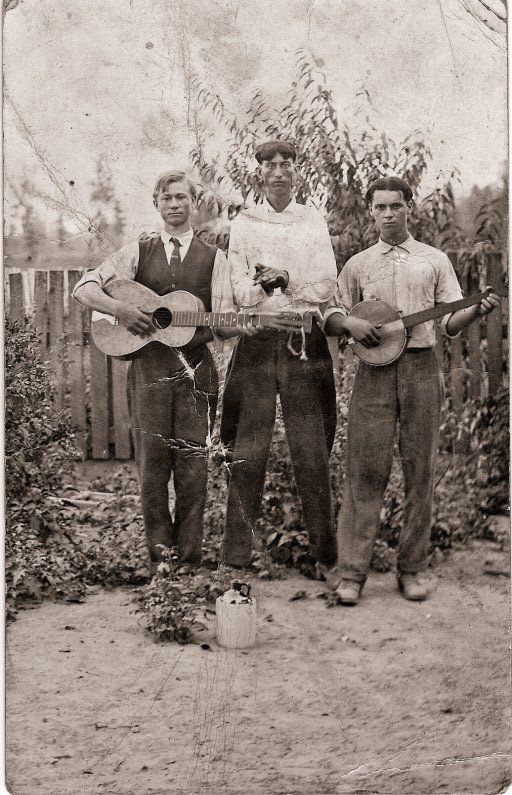

Of all my relatives, A.C. has the widest variety of occupations. He works as a foreman in auto factories, on farms as a teamster, in lumberyards for his father, and as a cook in a restaurant. This last job is one he shared with his daughter, my grandmother.

A.C. probably moved to Detroit after his divorce from Mellie around 1945. In the Flint phone directory after this, Mellie claims she is Albert’s widow. I notice she still lives on 2nd Street with AC’s stepsister Amnier Craig’s family until her marriage to Roy Wood.

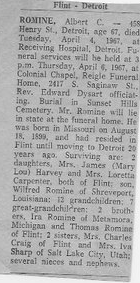

I can’t find him in any censuses or phone directories in Detroit. His obituary says he lived on Henry Street. He died of lung cancer on April 4, 1967. He was buried in Flint.

Sources

US Federal Censuses

(1900 – 1920, 1940)

Stoddard, New Madrid, and Mississippi Counties, Missouri. Accessed on Ancestry.com and Familysearch.org.

Application for Social Security Account Number

Albert Clayton Romine: 384-07-0921. Personal Records. Received from NARA.

Missouri, County Marriage, Naturalization, and Court Records, 1800-1991

U.S., Marriage Records, 1911-1914. New Madrid County, Missouri; Albert C Roumine [sic] and Elizabeth Lewis, p 418 of 493. Accessed on Familysearch.com.

“Divorces,” The Weekly Record (New Madrid, MO), 28 May 1926, p 9. Newspapers.com.

Missouri, County Marriage, Naturalization, and Court Records, 1800-1991

New Madrid County, Missouri; A. C. Romine and Mellie Opal Herndon [sic], p 275 of 950. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

U.S. WWI Draft Registration Card, 1917-1918. Albert Clayton Romine, New Madrid County, Draft Card R, 24-3-24 C. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

Michigan Department of Health, Divorce Record. Mellie Romine and Albert C. Romine. State Office number 25 14472. Personal Records.

Flint City Directories, 1935-1945. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947. Albert Clayton Romine, Michigan, Reed-Rossow. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

Michigan Certificate of Death.

Albert C. Romine as reported by Amnier Craig. Personal records. Certificates, 4860: Detroit (Michigan).

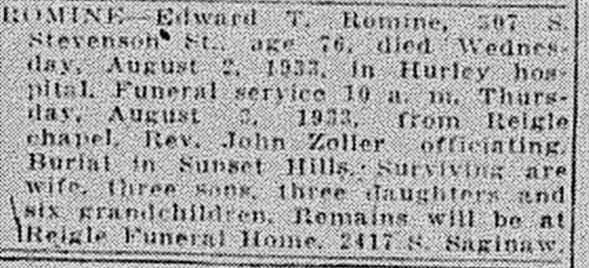

TRANSCRIPT from The Flint Journal (Flint, Michigan), 6 Jan 1963, p. D7:

TRANSCRIPT from The Flint Journal (Flint, Michigan), 6 Jan 1963, p. D7: