My great-grandmother through her daughter, Bernice.

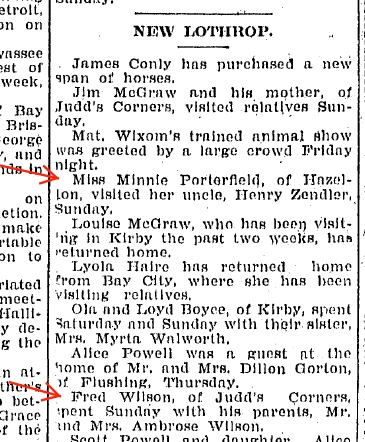

Minnie Mae Porterfield Wilson, my maternal great-grandmother, came into this world on May 29, 1885 in Hazelton Township, Shiawassee County, Michigan. She was the first of two children for Ellen Zendler and George Porterfield. Her brother John Wesley came along in 1889.

George was a farmer. The 1900 census states that he emigrated from Canada to the US in 1870, and that his father emigrated from Scotland. Ellen was also born in Canada, having emigrated in 1879 with her German father and English mother.

Another fact that sticks out on this census record is the name of her future husband and his family living a few houses away. I can only conclude they met because they were neighbors, or maybe they attended the same church. This area of Michigan is rural now; I imagine the closest neighbors during this time could be miles away.

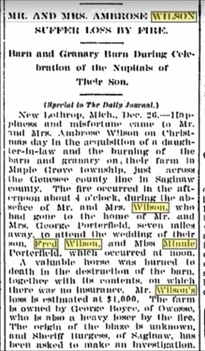

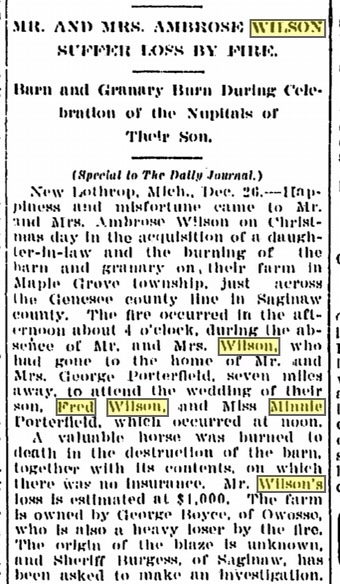

She married Fred Wilson on December 25, 1906 at her parents’ house. Her uncle, Samuel Porterfield, a local Methodist minister, officiated the wedding.

The couple had three children: two daughters and a son. They stayed in Hazelton Township until 1917 or 1918, when the family is listed on Becker Street near Corunna Road in Flint. Two years later, they are in Flushing. I think Fred got a job at an auto plant and wanted to move closer to work. He continued to farm though when he lived in Flushing.

Minnie and Fred lived in Flushing and Swartz Creek the rest of their lives: first on Dillon Road, then Beecher, then 2444 Seymour Road.

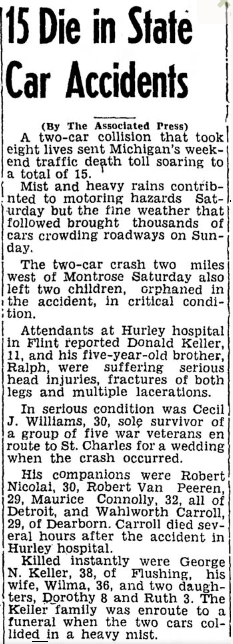

In 1947, the family endured a tragedy when daughter Wilma, her husband, and two of their four kids died in a car crash. The two survivors of the crash lived with Fred and Minnie on the Seymour Road farm.

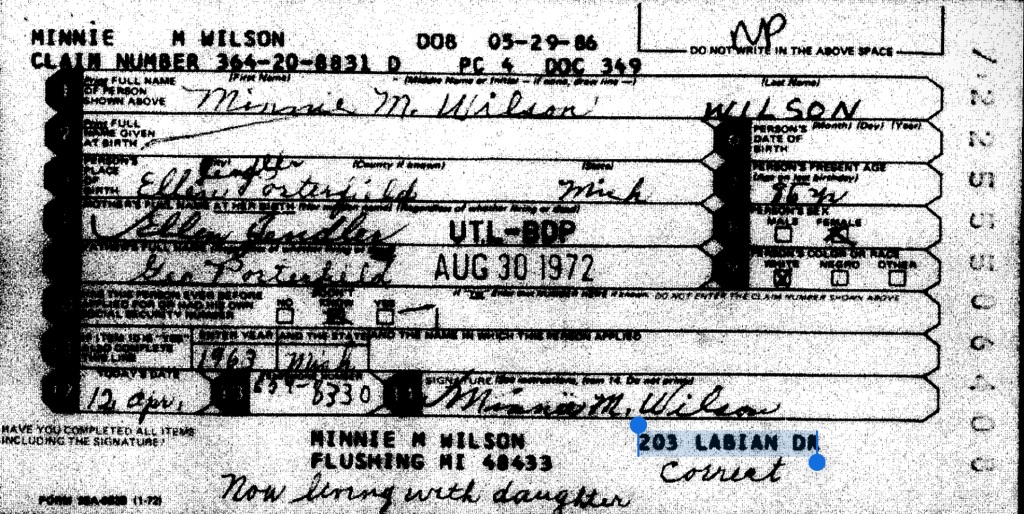

Minnie and Fred celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary on December 25, 1966. When Fred passed away on May 28, 1967, Minnie moved in with her daughter Bernice on Labian Drive in Flushing.

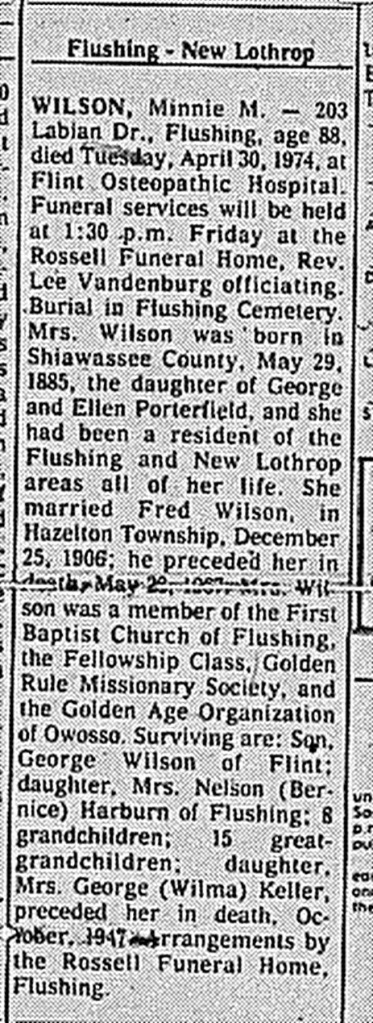

She passed on April 30, 1974, in Flushing at the age of 88 from heart failure. She was buried in Flushing City Cemetery. She was a member of the First Baptist Church of Flushing, the Fellowship Class, Golden Rule Missionary Society, and the Golden Age Organization of Owosso.

Notable Facts

Minnie Porterfield Wilson shouldn’t be confused with her cousin, Minnie Porterfield Barnes Canfield Robinson, the daughter of James and Teresa Boyce Porterfield, who lived nearby and was 2 years older.

My mother remembers going to Minnie’s house and seeing tons of baked goods in her kitchen.

Sources

Ontario Canada Births, 1869-1913

Archives of Ontario; Series: MS929; Reel: 11. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

Canada Censuses

(1881 – 1911)

Hibbert, Perth County, Ontario; Hensall, Huron County, Ontario. Accessed on Library and Archives Canada or Familysearch.org.

US Federal Censuses

(1920 – 1940)

Genesee County, Michigan. Accessed on Ancestry.com or Familysearch.org.

Ontario Canada Marriages, 1801-1928

(Archives of Ontario, MS932, Reel: 83)

Accessed on Ancestry.com.

US Border Crossings From Canada

National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Manifests of Passengers Arriving at St. Albans, VT, District through Canadian Pacific and Atlantic Ports, 1895-1954; National Archives Microfilm Publication: M1464. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

Michigan, Death Records, 1867-1950

File Number 011077. Accessed on Ancestry.com. Ordered on seekingmichigan.org now Michiganology.org. Personal records.

“Obituaries and Funeral Notices”,

Flint Journal, Flint, Michigan, September 24, 1946, Page: 18; Col 6; Item 7. Personal records. Accessed at Flint Public Library.

“The William Harburn Family in Michigan”,

Flushing Sesquicentennial History 1835-1987, Flushing Area Historical Society (Michigan), Vol. 2 (1987). Page 166. Personal records.

Findagrave.com

“William M Harburn,” ID#62465870, Flushing City Cemetery, Flushing, Genesee, Michigan

Family Stories