MRS. LOUIS CLAYTON JAMES

She Has a Grievance Which She Has Brought All the Way From Lincoln County, Nebraska And now She Airs It for the Readers of “The Nonpareil.”

There is a woman in Council Bluffs who has a story. Her name is Mrs. Louis Clayton James, and besides her story she has four small children. She came here Sunday from Lincoln county, Neb., and is living with her divorced husband’s mother at the corner of Tenth street and Avenue H. Mrs. James, the mother, has a number of children, and the two families are living in a two room hovel. Mrs. Louis Clayton James is very bitter against her husband-who-was. She declares that she will have him arrested to-day for securing a divorce from her by false testimony. She consulted an attorney yesterday and if the story she told a Nonpareil man last night is true, Mr. Louis Clayton James had better elope at once. Her story is rather difficult to follow, because Mother James was present during the interview and chimed in so often in defense of her “darling boy” that at times the air was a bedlam of confused prattle. Here’s what the reporter heard:

“Mrs. James is my name an’ my husband’s name’s Lou James.”

“Taint so,” remarked Mother James, “my son’s name aint ‘Lou’ James; It’s Louis Clayton James an’ I want it put in th’ paper that away.”

“Mother, I wish you–”

“I aint your mother,” said Mother James in frigid tones, “an’ I don’t want t’ hear no more of your motherin’ me.”

. . . Miss Louis Clayton James continued:

“Me an’ my husband we went to Nebraska three years ago an’ we took up a claim in Lincoln county. Not quite a year gone he told me he was tired o’ me an’ he left me, so he did, an’ him [come] back t’ Council Bluffs. I didn’t hear no more from him an’ only twiced he sent me money. He sent me $1.50 onced an’ $2 ‘nother time, an’–”“No look ahere,” protested Mother James, “that’s a lie. He sent you $2 th’ first time an’–”

“He didn’t nuther, he–”

“He did, I say–”

The reporter called time and Mrs. Louis Clayton James proceeded:

“Last month I sent my little darter t’ Council Bluffs t’ visit an’ she [sent] him back t’ me in Nebraska all beat on an’ bruised an’ my husband, he–”

“No he didn’t nuther,” screamed Mother James, “he didn’t do nothin’ o’ th’ sort. He never beat the child, an’ I can swear he didn’t.”

“Well that’s nuther here nor there,” said Mrs. Louis Clayton James, “so I’ll drop it.”

“Your’d better drop it,” chimed in the aggrieved Mother James, and the woman went on with her story.

“I didn’t know just how I was fixed wi’ my husband so I pulled up an’ [come] back t’ Council Bluffs an’ now I find he’s got a divorce from me an’ is married again t’ a Kissell woman, who is janitor o’ the’ Hall school. He got th’ divorce on th’ grounds that I ‘aint a good woman an’ I am told by neighbors that he married th’ Kissell woman afore he got th’ divorce from me, an’ if that’s so I–”

“I know better’n that,” said Mother James. “He didn’t marry Miss Kissell afore he got his divorce from you. I know this because we went down t’th’ court house one evenin’ an’ paid $10 for the divorce an’ then he went an’ got married;”

“I don’t care nothin’ ’bout what you say. That’s what th’ neighbors tell me,” continued Mrs. James. “An’ then I’m told that he paid a man t’ swear I was a bad woman, an’ when I find out th’ name o’ th’ man I’ll make him dance. I went down t’ th’ court house an’ looked at th’ records, and they only show that he was given a divorce; they don’t say what for. I’ve seen Lawyer Boulton, I have, an’ I’m go’n’t make it hot for that man. I’ve seen th’ chief o’ police too, an’ I’m goin’ t’ have James arrested too. He just wanted t’ get rid o’ me an’ I’m goin’ t’ get even with him an’ that huzzy he married.”

Mrs. Louis Clayton James and Mother James commenced another round and the reporter sneaked off, leaving them to fight it out.

Despite the journalists’ sensationalism and his attempts to make my ancestors sound like bumpkins, I was pretty excited to find this article and even more excited to prove that these two are my ancestors. The shady Louis is my great-granduncle, and “Mother James” is my 2nd great grandmother, Olivia. I feel like this gives me an idea of who she was: fiercely loyal to her children and able to speak her mind. She was the kind of woman who told the journalist exactly how her son’s name should appear in the newspaper and the journalist listened. As for how this situation resolved, here’s one more document:

Transcript:

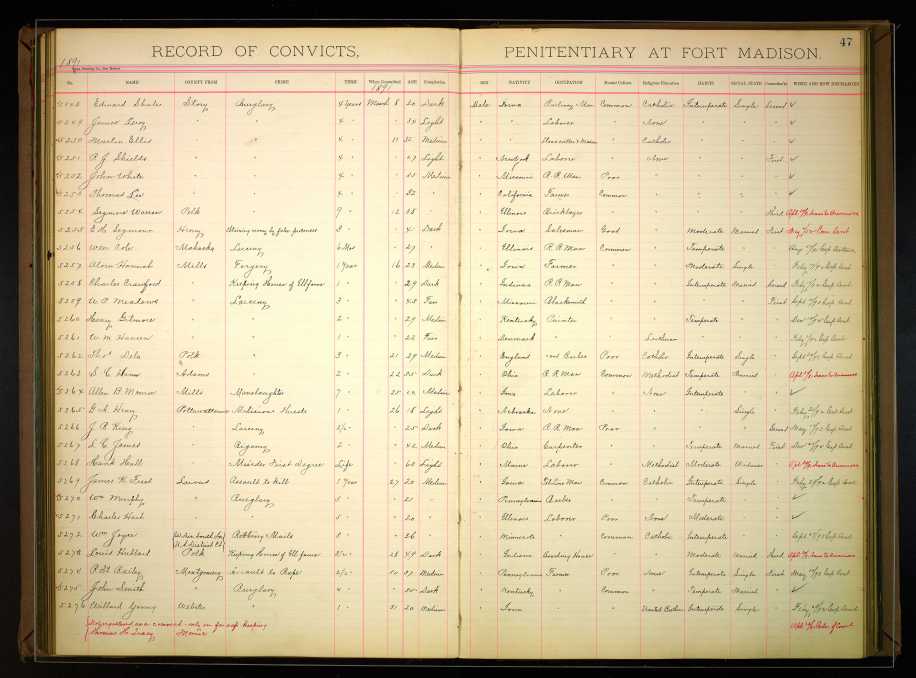

Line 5267

Name: L C James

Sex: Male

Birth year: 1849

Age: 42

Occupation: Carpenter

Birth state: Ohio

County of Residence: Pottawattamie

Date of incarceration: 26 Mar 1891

Term of sentence: 2 yrs

Charge: Bigamy

(Click for genealogical sources)

Writing for Amy Johnson Crow’s #52Ancestors. The prompt was Strong Women.

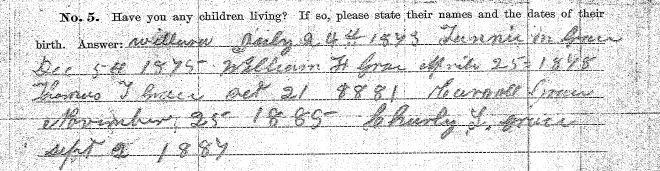

[transcript: Have you any living children? If so, please state their names and the dates of their birth. Answer: Willard July 24th 1873, Fannie M. Grace Dec 5th 1875, William H Grace Mar 25 1878…]

[transcript: Have you any living children? If so, please state their names and the dates of their birth. Answer: Willard July 24th 1873, Fannie M. Grace Dec 5th 1875, William H Grace Mar 25 1878…]